Lost Objects: Berggasse 19 and Absence in the Space of Psychoanalysis

The Freudian Legacy Today, ed. Dina Georgis, Sara Matthews, James Penney, The Canadian Network for Psychoanalysis and Culture. 2015

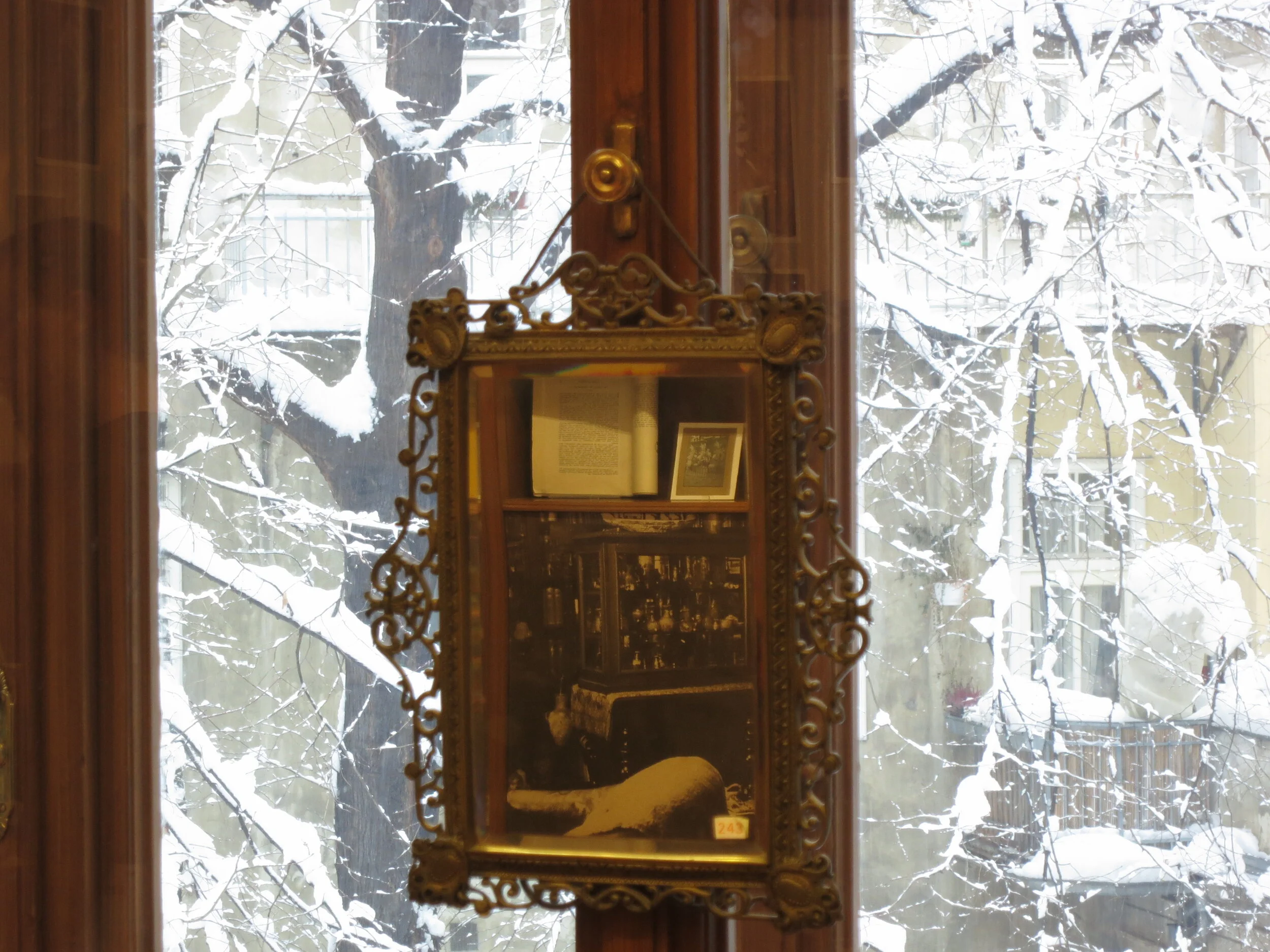

This paper analyzes the Freudian legacy at what is arguably its founder’s primary site of memorialization: The Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna. How Freud is memorialized at Berggasse 19, where he lived and practiced for forty-seven years, can tell us not only about the psychodynamics of institutional spaces of public memory, but also about the kinds of promises and threats that psychoanalysis poses for the culture at large. Whereas the Freud Museum in London is characterized by its collection of all the “good” Freudian artifacts, including the famed couch, the Vienna Museum can be said to be haunted by its “lost objects.” I will examine some of the ways in which the unconscious is materialized and de-materialized in the Vienna Museum. I argue that Freud’s escape from Nazi persecution and exile from Austria casts his former home and offices into a space of irremediable loss. The Museum not only marks this loss but is also constituted by it. Its apparent emptiness reflects Freud’s evacuation, along with his family, followers, and treasured belongings. This “constitutive absence” engenders an intractable melancholia, one that I propose has fetishistic undertones (Mayer 2009, 140). I will concentrate on the role of photography in organizing the Museum as a “way of seeing” that is paradoxically based less on visual presence than on its absence (Alpers 1991). The framing of the Museum’s “lost objects,” specifically through Edmund Engelman’s iconic photographs, reveals how substitute objects are enlisted in an effort to mitigate loss, but how absence nevertheless prevails. The historical conditions of psychoanalysis’s emergence and its contemporary conditions at Berggasse 19 lead me to conclude that absence occupies the very heart of psychoanalysis.